I can already get a glimpse of some sails from the Interstate Highway 15 which goes from California to Nevada. All that can be seen are bright triangles, because the wheels and the hulls are obscured by refraction. Up ahead of me, on a desert plain which is sprinkled here and there with low bushes and leans against steep hills, lies the building complex where we will be staying. If you live in California, this is the nearest place to come to if you are looking to play whatever you want, whether it be slot machines, poker, black jack or roulette. There’s the state line, and right there as you pass into Nevada, where gambling is legal, you come across three enormous hotels with their respective casinos. We have opted for the least expensive of the three: the Whiskey Pete’s.

In all deserts there are markings, steel signposts that indicate the correct route to follow. Here, where there’s practically no chance of getting lost, they serve mainly as an aid to traffic. Nevertheless, in this environment which is so different from that to which we are used, it makes sense to be careful. I follow the trace of the tyretracks to a sign that asks for a reduction in speed: NO DUST. I’ve reached the field. I see before me some of the most sophisticated crafts, with their streamlined and shrouded masts, as well as some of the simplest, with their sail set on , quietly resting, upside down, so that they won’t be able to start sailing on their own. I study the architecture, drinking in every last detail. I knock on the door of the race organizers’ motorhome, but there’s nobody there.

No sign of the President of the North American Sailing Association, Kent Hatch, with whom I have kept in contact over the preceding months. So, I still don’t know for sure if there’s a craft for me. I explore some more. Amidst the weathercocks, in the form of pigs, carrots, I can see stars and stripes flags, the anemometers, more landyachts and, down at the end of the field, the Ironduck, which holds the undisputed speed record. From the photos I downloaded from the official Nalsa site I thought it was shinier, but for all that the opaque and somewhat damaged paintwork and the adhesive tape that ties the joints together take nothing away from the fascination of this aerodynamic giant which with its wing has managed to reach a speed of 187 kms per hour.

No sign of the President of the North American Sailing Association, Kent Hatch, with whom I have kept in contact over the preceding months. So, I still don’t know for sure if there’s a craft for me. I explore some more. Amidst the weathercocks, in the form of pigs, carrots, I can see stars and stripes flags, the anemometers, more landyachts and, down at the end of the field, the Ironduck, which holds the undisputed speed record. From the photos I downloaded from the official Nalsa site I thought it was shinier, but for all that the opaque and somewhat damaged paintwork and the adhesive tape that ties the joints together take nothing away from the fascination of this aerodynamic giant which with its wing has managed to reach a speed of 187 kms per hour.

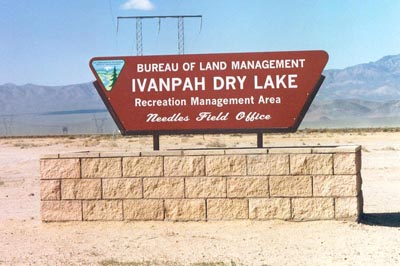

The wind is variable. It rises and then dies without warning, leaving you still to while away the time, trailing your fingers on the hard surface of Ivanpah Dry Lake. Then it blows again, and in those ten minutes or so the whole world turns upside down. I’m worried, not so much about what I’m doing or about how I’m controlling the Manta, as about what is going on around me. How are you supposed to stay calm, to have a precise landmark , how are you supposed to know in how many seconds a six or seven meter wide beast of Class II going at 100 kms per hour might cross your way? At the beginning I keep out of the way so as not to cause any problems. Then I start to understand the game, how much space you need and how much the big guys require in order to steer. The most treacherous yachts turn out to be the Five Square Meter – more or less the same size as the Manta, yet they reach much greater speeds and, more to the point, they are all over the place. Every time you turn your head to see if you can tack there’s one right there, with its pilot almost lost inside a synthetic shell, and with those so-called crazy wheels inevitably tilted at an absurd angle.

Monday, 9am. The briefing. A welcome and details of the weather forecast for the day. Then on to the rules of the regatta. Here’s the thing, though. As soon as the briefing ends, innumerable little groups form, wherein race strategies are explained in a whole manner of ways. There are fingers drawing in the air and twigs busily tracing on the desert sand: starting line, marks, the nearest one with a doodad called windflasher, a little mirror that rotates in the wind and whose reflection indicates, or at least it should, the position, the furthest one discerned by a weathercock, and the finishing line. The starting grid is drawn from lots and is in a way a metaphor of one’s destiny. For the first race my initial task is to find position No. 2 and I find it marked on a metal sign attached to the rope that represents the starting line. As the wind is frequently changing direction there are two ropes with signs denoting starting positions. If the wind is coming from the south then you have to use the other rope adding 30 to the drawn position. It shouldn’t really have been difficult to understand what route to take to return to the camp without being run over by other crafts which are being propelled by wind blowing from different directions. But you end up thinking about it and when you are not used to certain situations it takes a while to attain an even moderate sense of security. Then the rest will follow.

Monday, 9am. The briefing. A welcome and details of the weather forecast for the day. Then on to the rules of the regatta. Here’s the thing, though. As soon as the briefing ends, innumerable little groups form, wherein race strategies are explained in a whole manner of ways. There are fingers drawing in the air and twigs busily tracing on the desert sand: starting line, marks, the nearest one with a doodad called windflasher, a little mirror that rotates in the wind and whose reflection indicates, or at least it should, the position, the furthest one discerned by a weathercock, and the finishing line. The starting grid is drawn from lots and is in a way a metaphor of one’s destiny. For the first race my initial task is to find position No. 2 and I find it marked on a metal sign attached to the rope that represents the starting line. As the wind is frequently changing direction there are two ropes with signs denoting starting positions. If the wind is coming from the south then you have to use the other rope adding 30 to the drawn position. It shouldn’t really have been difficult to understand what route to take to return to the camp without being run over by other crafts which are being propelled by wind blowing from different directions. But you end up thinking about it and when you are not used to certain situations it takes a while to attain an even moderate sense of security. Then the rest will follow.

On Monday I don’t get a chance to race. The wind rises late and the Manta Twins are the last on the schedule. But Tuesday is a good day for me, the wind conditions being just right for a debut. I’m sitting there, lined up, when Dave, the guy who lent me the yacht, arrives at my shoulder and, perhaps because of the tension, I manage to understand an entire sentence from beginning to end without having to ask for it to be repeated. He says “Do you feel the adrenaline pumping?” Yes. The green flag is lowered and I take my time starting off so as to see what the others are doing. I see that the gusts are raising the wheels of the crafts in front of me and wait my turn on the wind corridor while trying to stay on two wheels as long as possible. Can you go faster balanced on two wheels? I don’t know, but it sure is more fun that way. And this is really one of those things that make life worth living. Wednesday is the same thing, and it’s hard not to get to enjoy it. I start off well, but when the others begin to tack I keep out of their way and lose ground. Wheels up, a touch of duelling, not bad at all. Thursday, well, the TV had said it. They got it and the wind came up. Got to be careful today. It’s a disaster. I can’t seem to concentrate, I’m not in harmony with the Manta and my manoevres are clumsy. In these conditions, the regattas follow one upon the other without a break. In the first I get lost and end up near some bushes, but then I start again and manage to finish. The second one goes even worse. I set out more concentrated, intending to carry out more tacks than before on my way to the first mark, but my hands lose their grip of the sheet and when I tried to work it into the block I get the feeling that something isn’t right. I’m given a hand by Cha Cha, a guy from Copenhagen who seems to handle everything with a true enviable spirit. Now he is competing with another person on the seat while he holds the sheet with one hand and takes photos with the other, a position he has maintained from the very first regatta. He’s nothing less than a volcano of positive energy and a sportsman in the real sense of the word. Anyway, I withdraw from the competition, I don’t want to cause damage. On Friday it is impossible to race. The wind has grown and significantly it raises a great deal of dust. There are a few landyachts around the lake, the Ironduck amongst them. Photoelectric cells have been set to record the speed. The Ironduck is at full speed when some white thing comes off: almost a third of its sail has broken. Game over. Only the prize-giving ceremony is left to be enjoyed. We sit at the table with some pilots who come from the Atlantic coast of the United States. They usually sail on ice. It must be different from a desert, isn’t it? “Well, I think so, mostly because the ice could break and you can fall into the lake.” Does it happen very often? “It happened to me, to him and to him as well.” We are sort of sorry for being the only ones sitting at that table who did not fall into the icy lake.